Ngati, here is the reply I made to your post if you can be bothered reading. There was a whole crapload of other stuff I wrote but this is the only post I saved to notepad :/

From what I was reading, Einstein vehemently disliked quantum mechanics. He liked to think of the universe being probabilistic and nothing changed but was always fundamentally the same. He could never really accept that particular concept of quantum theory.

Max Planck on the otherhand, the founder of quantum theory, was quite religious.

I'm sure Einstein probably made a lot of contradictory statements throughout his life, I think that's somewhat understandable for what was probably one of the most intelligent scientists in recent history (for example, there was that quote where he had some harsh things to say about religion, but I think he might have actually had an admiration for the core concept of religions) - I already knew that he didn't believe in a personal God (that plans our daily lives and performs miracles ect.), but he still believed in God and couldn't conceive of a universe that existed without one.

I think when Einstein was talking about God, it might have been more of a metaphor than anything. Definately not the exact same idea of God that Judeo-Christians believe in, but it's going back to the thing I posted a while back about we all approach the same thing, just in different ways.

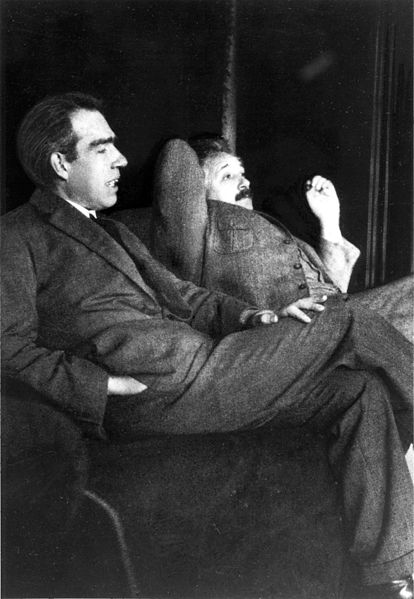

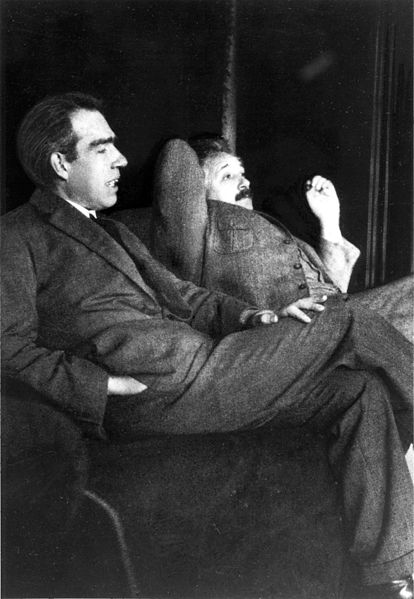

'God does play dice', it seems, yes. Neils Bohr, whom was apparently another scientist working on quantum mechanics at the time that Einstein made the comment 'God does not play dice' said to Einstein, 'Stop telling God what to do with his dice!" But he spent the better part of his last few years trying to dismiss the unpredictability of quantum mechanics with his grand Theory of Everything (something scientists are still working on today) that he thought would be the equivalent of 'reading the mind of God.'

"I'm not interested in this phenomenon or that phenomenon. I want to know how God created this world...I want to know his thoughts; the rest are details,"

It's fair to say he may have lost the plot just a little bit in his remaining years, but he also came up with the theory of relativity and E=mc2 aswell as numerous other scientific discoveries so he is someone to be respected even if he was unable to accept the discovery of quantum theory.

He also stood up and applauded, and said 'This is the most beautiful and satisfactory explanation of creation I have ever witnessed!' when George Lemaitre explained his theory of the 'primeval atom' (Big Bang) to him, and admitted the mistakes he had made with some of his own theories.

Awesome guy.

pic, Neils Bohr and Einstein discussing quantum mechanics:

I don't quite understand quantum mechanics and quantum theory, it's a bit complex for me.

Krasher - Priests can drop a stinky...

What the hell is that supposed to mean anyway?

It certainly does seem like the more science uncovers, the easier it becomes to deny the existence of God.

As far as I know a lot of modern scientists these days still believe they are uncovering the underlying mechanics of how God may have created the universe and nature. They probably just have many varying ideas of what God is or might actually be.

There is an interesting concept of Nonoverlapping Magisteria (NOMA) which was proposed by the evolutionary biologist, Stephen Gould:

In his book Rocks of Ages (1999), Gould put forward what he described as "a blessedly simple and entirely conventional resolution to ... the supposed conflict between science and religion."[46] He defines the term magisterium as "a domain where one form of teaching holds the appropriate tools for meaningful discourse and resolution"[46] and the NOMA principle is "the magisterium of science covers the empirical realm: what the Universe is made of (fact) and why does it work in this way (theory). The magisterium of religion extends over questions of ultimate meaning and moral value. These two magisteria do not overlap, nor do they encompass all inquiry (consider, for example, the magisterium of art and the meaning of beauty)."[46]

In his view, "Science and religion do not glower at each other...[but] interdigitate in patterns of complex fingering, and at every fractal scale of self-similarity."[46] He suggests, with examples, that "NOMA enjoys strong and fully explicit support, even from the primary cultural stereotypes of hard-line traditionalism" and that it is "a sound position of general consensus, established by long struggle among people of goodwill in both magisteria."[46]

Also in 1999, the National Academy of Sciences adopted a similar stance. Its publication Science and Creationism stated that "Scientists, like many others, are touched with awe at the order and complexity of nature. Indeed, many scientists are deeply religious. But science and religion occupy two separate realms of human experience. Demanding that they be combined detracts from the glory of each."[47]